Every noun in Urbit is an atom or a cell. This module will elaborate how we can use this fact to locate data and evaluate code in a given expression. It will also discuss the important list mold builder and a number of standard library operations.

Trees

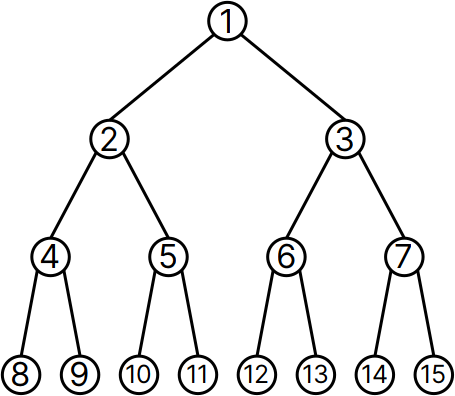

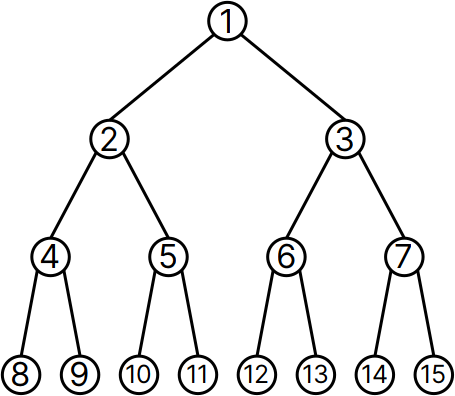

Every noun in Urbit is a either an atom or a cell. Since a cell has only two elements, a head and a tail, we can derive that everything is representable as a binary tree. We can draw this layout naturally:

A binary tree has a single base node, and each node of the tree may have up to two child nodes (but it need not have any). A node without children is a “leaf”. You can think of a noun as a binary tree whose leaves are atoms, i.e., unsigned integers. All non-leaf nodes are cells. An atom is a trivial tree of just one node; e.g., 17.

For instance, if we produce a cell in the Dojo

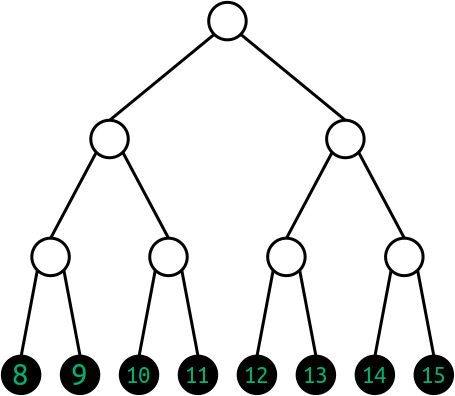

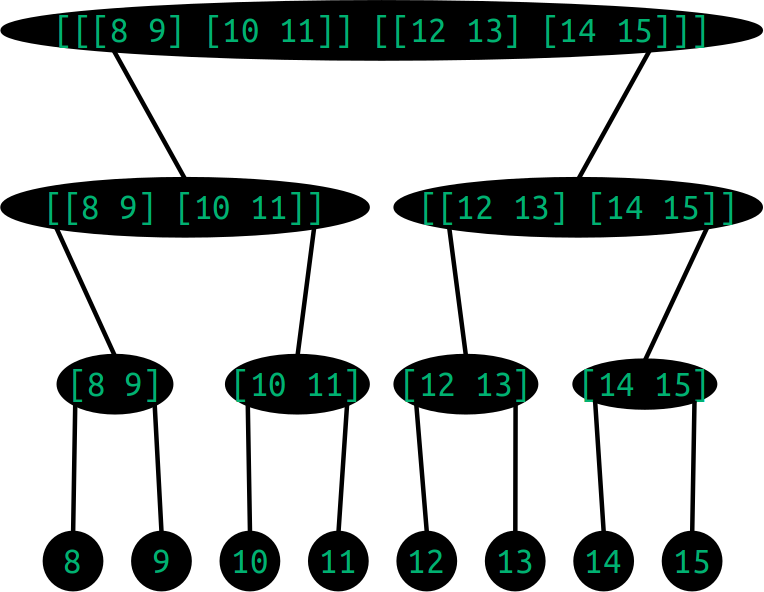

> =a [[[8 9] [10 11]] [[12 13] [14 15]]]

it can be represented as a tree with the contents

We will use the convention in these graphics that black-text-on-white-circle represents an address, and that green-text-on-black-circle represents the content at that address. So another way to represent the same data would be this:

When we input the above cell representation into the Dojo, the pretty-printer hides the rightwards-branching [] sel/ser brackets.

> [[[8 9] [10 11]] [[12 13] [14 15]]][[[8 9] 10 11] [12 13] 14 15]

We can refer to any data stored anywhere in this tree. The numbers in the labeled diagram above are the numerical addresses of the tree, and may be extended indefinitely downwards into ever-deeper tree representations.

Most of any possible tree will be unoccupied for any actual data structure. For instance, lists (and thus tapes) are collections of values which occupy the tails of cells, leading to a rightwards-branching tree representation. (Although this may seem extravagant, it has effectively no bearing on efficiency in and of itself—that's a function of the algorithms working with the data.)

Exercise: Map Nouns to Tree Diagrams

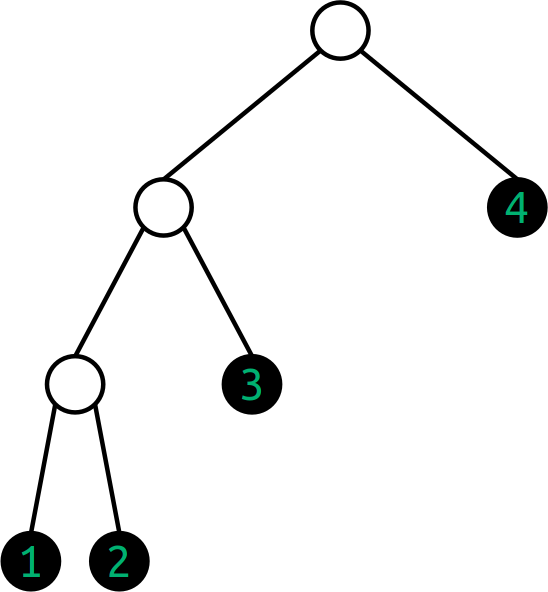

Consider each of the following nouns. Which tree diagram do they correspond to? (This is a matching exercise.)

Noun Tree Diagram 1. [[[1 2] 3] 4]A.

2. [[1 2] 3 4]B.

3. [1 2 3 4]C.

Exercise: Produce a List of Numbers

Produce a generator called

list.hoonwhich accepts a single@udnumbernas input and produces a list of numbers from1up to (but not including)n. For example, if the user provides the number5, the program will produce:~[1 2 3 4].|= end=@=/ count=@ 1|-^- (list @)?: =(end count)~:- count$(count (add 1 count))In the Dojo:

> +list 5~[1 2 3 4]> +list 10~[1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9]> +list 1~OK, we've seen these runes before. This time we want to focus on the list, the thing that's being built here.

This program works by having each iteration of the list create a cell. In each of these cells, the head—the cell's first position—is filled with the current-iteration value of

count. The tail of the cell, its second position, is filled with the product of a new iteration of our code that starts at|-. This iteration will itself create another cell, the head of which will be filled by the incremented value ofcount, and the tail of which will start another iteration. This process continues until?:branches to~(null). When that happens, it terminates the list and the expression ends. A built-out list of nested cells can be visualized like this:[1 [2 [3 [4 ~]]]]./ \1 ./ \2 ./ \3 ./ \4 ~

Tuples as Trees

What we've been calling a running cell would more conventionally be named a tuple, so we'll switch to that syntax now that the idea is more familiar. Basically it's a cell series which doesn't necessarily end in ~.

Given the cell [1 2 3 4 ~] (or equivalently ~[1 2 3 4], an irregular form for a null-terminated tuple or list), what tree address does each value occupy?

![A binary tree of the cell [1 2 3 4 ~].](https://media.urbit.org/docs/userspace/hoon-school/binary-tree-1234.png)

At this point, you should start to be able to work this out in your head, at least for the first few rows. The + lus operator can be used to return the limb of the subject at a given numeric address. If there is no such limb, the result is a crash.

> =data ~[1 2 3 4]> +1:data[1 2 3 4 ~]> +2:data1> +3:data[2 3 4 ~]> +4:datadojo: hoon expression failed> +6:data2> +7:data[3 4 ~]> +14:data3> +15:data[4 ~]> +30:data4> +31:data~

Lists as Trees

We have used lists incidentally. A list is an ordered arrangement of elements ending in a ~ (null). Most lists have the same kind of content in every element (for instance, a (list @rs), a list of numbers with a fractional part), but some lists have many kinds of things within them. Some lists are even empty.

> `(list @)`['a' %b 100 ~]~[97 98 100]

(Notice that all values are converted to the specified aura, in this case the empty aura.)

A list is built with the list mold. A list is actually a mold builder, a gate that produces a gate. This is a common design pattern in Hoon. (Remember that a mold is a type and can be used as an enforcer: it attempts to convert any data it receives into the given structure, and crashes if it fails to do so.) Lists are commonly written with a shorthand ~[]:

> `(list)`~['a' %b 100]~[97 98 100]

> `(list (list @ud))`~[~[1 2 3] ~[4 5 6]]~[~[1 2 3] ~[4 5 6]]

True lists have i and t faces which allow the head and tail of the data to be quickly and conveniently accessed; the head is the first element while the tail is everything else. If something has the same structure as a list but hasn't been explicitly labeled as such, then Hoon won't always recognize it as a list. In such cases, you'll need to explicitly mark it as such:

> [3 4 5 ~][3 4 5 ~]> `(list @ud)`[3 4 5 ~]~[3 4 5]> -:!>([3 4 5 ~])#t/[@ud @ud @ud %~]> -:!>(`(list @ud)`[3 4 5 ~])#t/it(@ud)

A null-terminated tuple is almost the same thing as a list. (That is, to Hoon all lists are null-terminated tuples, but not all null-terminated tuples are lists. This gets rather involved in subtleties, but you should cast a value as (list @) or another type as appropriate whenever you need a list. See also ++limo which explicitly marks a null-terminated tuple as a list.)

Addressing Limbs

Everything in Urbit is a binary tree. And all code in Urbit is also represented as data. One corollary of these facts is that we can access any arbitrary part of an expression, gate, core, whatever, via addressing (assuming proper permissions, of course). (In fact, we can even hot-swap parts of cores, which is how wet gates work.)

There are three different ways to access values:

- Numeric addressing is useful when you know the address, rather like knowing a house's street address directly.

- Positional addressing is helpful when you don't want to figure out the room number, but you know how to navigate to the value. This is like knowing the directions somewhere even if you don't know the house number.

- Wing addressing is a way of attaching a name to the address so that you can access it directly.

Numeric Addressing

We have already seen numeric addressing used to refer to parts of a binary tree.

Since a node is either an atom (value) or a cell (fork), you never have to decide if the contents of a node is a direct value or a tree: it just happens.

Exercise: Tapes for Text

A tape is one way of representing a text message in Hoon. It is written with double quotes:

"I am the very model of a modern Major-General"

A tape is actually a (list @t), a binary tree of single characters which only branches rightwards and ends in a ~:

- What are the addresses of each letter in the tree for the Gilbert & Sullivan quote above? Can you see the pattern? Can you get the address of EVERY letter through

l?

Positional Addressing (Lark Notation)

Much like relative directions, one can also state “left, left, right, left” or similar to locate a particular node in the tree. These are written using - (left) and + (right) alternating with < (left) and > (right).

Lark notation can locate a position in a tree of any size. However, it is most commonly used to grab the head or tail of a cell, e.g. in the type spear (on which more later):

-:!>('hello Mars')

Lark notation is not preferred in modern Hoon for more than one or two elements deep, but it can be helpful when working interactively with a complicated data structure like a JSON data object.

When lark expressions resolve to the part of the subject containing an arm, they don't evaluate the arm. They simply return the indicated noun fragment of the subject, as if it were a leg.

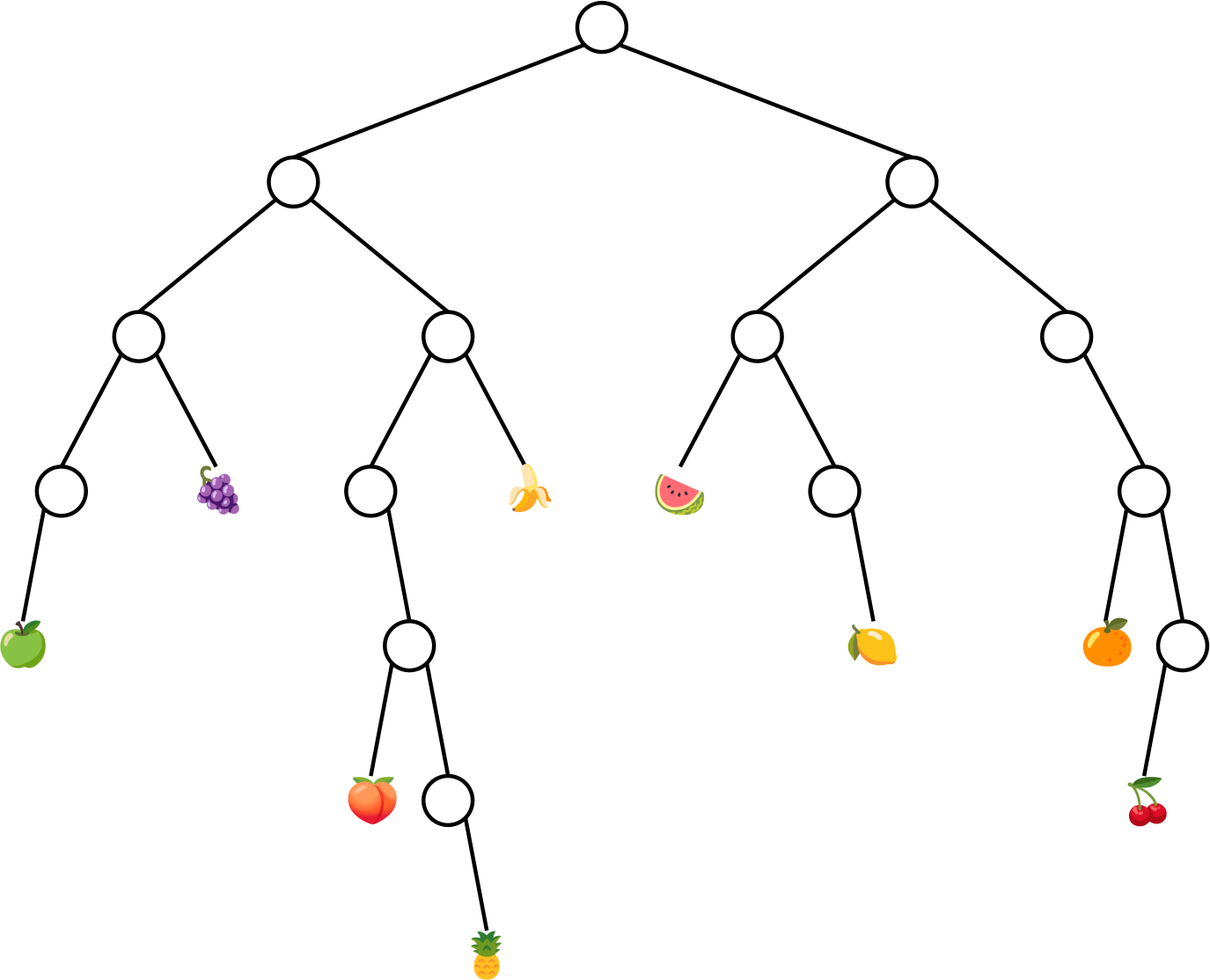

Exercise: Address the Fruit Tree

Produce the numeric and lark-notated equivalent addresses for each of the following nodes in the binary fruit tree:

- 🍇

- 🍌

- 🍉

- 🍏

- 🍋

- 🍑

- 🍊

- 🍍

- 🍒

There is a solution at the bottom of the page.

Exercise: Lark Notation

Use a lark expression to obtain the value 6 in the following noun represented by a binary tree:

./ \/ \/ \. ./ \ / \/ . 10 ./ / \ / \. 8 9 11 ./ \ / \5 . 12 13/ \6 7Use a lark expression to obtain the value

9in the following noun:[[[5 6 7] 8 9] 10 11 12 13].

Solutions to these exercises may be found at the bottom of this lesson.

Wings

One can also identify a resource by a label, called a wing. A wing represents a depth-first search into the current subject (context). A wing is a limb resolution path into the subject. A wing expression indicates the path as a series of limb expressions separated by the . character. E.g.,

inner-limb.outer-limb.limb

You can read this as inner-limb in outer-limb in limb, etc. Notice that these read left-to-right!

A wing is a resolution path pointing to a limb. It's a search path, like an index to a particular labeled part of the subject.

Here are some examples:

> c.b:[[4 a=5] b=[c=14 15]]14> b.b:[b=[a=1 b=2 c=3] a=11]2> a.b:[b=[a=1 b=2 c=3] a=11]1> c.b:[b=[a=1 b=2 c=3] a=11]3> a:[b=[a=1 b=2 c=3] a=11]11> b.a:[b=[a=1 b=2 c=3] a=11]-find.b.a> g.s:[s=[c=[d=12 e='hello'] g=[h=0xff i=0b11]] r='howdy'][h=0xff i=0b11]> c.s:[s=[c=[d=12 e='hello'] g=[h=0xff i=0b11]] r='howdy'][d=12 e='hello']> e.c.s:[s=[c=[d=12 e='hello'] g=[h=0xff i=0b11]] r='howdy']'hello'> +3:[s=[c=[d=12 e='hello'] g=[h=0xff i=0b11]] r='howdy']r='howdy'> r.+3:[s=[c=[d=12 e='hello'] g=[h=0xff i=0b11]] r='howdy']'howdy'

To locate a value in a named tuple data structure:

> =data [a=[aa=[aaa=[1 2] bbb=[3 4]] bb=[5 6]] b=[7 8]]> -:aaa.aa.a.data1

A wing is a limb resolution path into the subject. This definition includes as a trivial case a path of just one limb. Thus, all limbs are wings, and all limb expressions are wing expressions.

We mention this because it is convenient to refer to all limbs and non-trivial wings as simply “wings”.

Names and Faces

A name can resolve either an arm or a leg of the subject. Recall that arms are for computations and legs are for data. When a name resolves to an arm, the relevant computation is run and the product of the computation is produced. When a limb name resolves to a leg, the value of that leg is produced.

Hoon doesn't have variables like other programming languages do; it has faces. Faces are like variables in certain respects, but not in others. Faces play various roles in Hoon, but most frequently faces are used simply as labels for legs.

A face is a limb expression that consists of a series of alphanumeric characters. A face has a combination of lowercase letters, numbers, and the - character. Some example faces: b, c3, var, this-is-kebab-case123. Faces must begin with a letter.

There are various ways to affix a face to a limb of the subject, but for now we'll use the simplest method: face=value. An expression of this form is equivalent in value to simply value. Hoon registers the given face as metadata about where the value is stored in the subject, so that when that face is invoked later its data is produced.

Now we have several ways to access values:

> b=5b=5> [b=5 cat=6][b=5 cat=6]> -:[b=5 cat=6]b=5> b:[b=5 cat=6]5> b2:[[4 b2=5] [cat=6 d=[14 15]]]5> d:[[4 b2=5] [cat=6 d=[14 15]]][14 15]

To be clear, b=5 is equivalent in value to 5, and [[4 b2=5] [cat=6 d=[14 15]]] is equivalent in value to [[4 5] 6 14 15]. The faces are not part of the underlying noun; they're stored as metadata about address values in the subject.

> (add b=5 1)6

If you use a face that isn't in the subject you'll get a find.[face] crash:

> a:[b=12 c=14]-find.a[crash message]

You can even give faces to faces:

> b:[b=c=123 d=456]c=123

Duplicate Faces

There is no restriction against using the same face name for multiple limbs of the subject. This is one way in which faces aren't like ordinary variables:

> [[4 b=5] [b=6 b=[14 15]]][[4 b=5] b=6 b=[14 15]]> b:[[4 b=5] [b=6 b=[14 15]]]5

Why does this return 5 rather than 6 or [14 15]? When a face is evaluated on a subject, a head-first binary tree search occurs starting at address 1 of the subject. If there is no matching face for address n of the subject, first the head of n is searched and then n's tail. The complete search path for [[4 b=5] [b=6 b=[14 15]]] is:

[[4 b=5] [b=6 b=[14 15]]][4 b=5]4b=5[b=6 b=[14 15]]b=6b=[14 15]

There are matches at steps 4, 6, and 7 of the total search path, but the search ends when the first match is found at step 4.

The children of legs bearing names aren't included in the search path. For example, the search path of [[4 a=5] b=[c=14 15]] is:

[[4 a=5] b=[c=14 15]][4 a=5]4a=5b=[c=14 15]

Neither of the legs c=14 or 15 is checked. Accordingly, a search for c of [[4 a=5] b=[c=14 15]] fails:

> c:[[4 b=5] [b=6 b=[c=14 15]]]-find.c [crash message]

In any programming paradigm, good names are valuable and collisions (repetitions, e.g. a list named list) are likely. There is no restriction against using the same face name for multiple limbs of the subject. This is one way in which faces aren't like ordinary variables. If multiple values match a particular face, we need a way to distinguish them. In other words, there are cases when you don't want the limb of the first matching face. You can ‘skip’ the first match by prepending ^ to the face. Upon discovery of the first match at address n, the search skips n (as well as its children) and continues the search elsewhere:

> ^b:[[4 b=5] [b=6 b=[14 15]]]6

Recall that the search path for this noun is:

[[4 b=5] [b=6 b=[14 15]]][4 b=5]4b=5[b=6 b=[14 15]]b=6b=[14 15]

The second match in the search path is step 6, b=6, so the value at that leg is produced. You can stack ^ characters to skip more than one matching face:

> a:[[[a=1 a=2] a=3] a=4]1> ^a:[[[a=1 a=2] a=3] a=4]2> ^^a:[[[a=1 a=2] a=3] a=4]3> ^^^a:[[[a=1 a=2] a=3] a=4]4

When a face is skipped at some address n, neither the head nor the tail of n is searched:

> b:[b=[a=1 b=2 c=3] a=11][a=1 b=2 c=3]> ^b:[b=[a=1 b=2 c=3] a=11]-find.^b

The first b, b=[a=1 b=2 c=3], is skipped; so the entire head of the subject is skipped. The tail has no b; so ^b doesn't resolve to a limb when the subject is [b=[a=1 b=2 c=3] a=11].

How do you get to that b=2? And how do you get to the c in [[4 a=5] b=[c=14 15]]? In each case you should use a wing.

We say that the inner face has been shadowed when an outer name obscures it.

If you run into ^$, don't go look for a ^$ ketbuc rune: it's matching the outer $ buc arm. ^$ is one way of setting up a %= centis loop/recursion of multiple cores with a |- barhep trap nested inside of a |= bartis gate, for instance.

Solution #1 in the Rhonda Numbers tutorial in the Hoon Workbook illustrates using ^ ket to skip $ buc matches.

Limb Resolution Operators

There are two symbols we use to search for a face or limb:

.dot resolves the wing path into the current subject.:col resolves the wing path with the right-hand-side as the subject.

Logically, a:b is two operations, while a.b is one operation. The compiler is smart about : col wing resolutions and reduces it to a regular lookup, though.

What %= Does

Now we're equipped to go back and examine the syntax of the %= centis rune we have been using for recursion: it resolves a wing with changes, which in this particular case means that it takes the $ (default) arm of the trap core, applies certain changes, and re-evaluates the expression.

|= n=@ud|-~& n?: =(n 1)n%+ muln$(n (dec n))

The $() syntax is the commonly-used irregular form of the %= centis rune.

Now, we noted that $ buc is the default arm for the trap. It turns out that $ is also the default arm for some other structures, like the gate! That means we can cut out the trap, in the factorial example, and write something more compact like this:

|= n=@ud?: =(n 1)1(mul n $(n (dec n)))

It's far more common to just use a trap, but you will see $ buc used to manipulate a core in many in-depth code instances.

Expanding the Runes

|= bartis produces a gate. It actually expands to

=| a=spec|% ++ $ b=hoon--

where =| tisbar means to add its sample to the current subject with the given face.

Similarly, |- barhep produces a core with one arm $. How could you write that in terms of |% and ++?

Example: Number to Digits

- Compose a generator which accepts a number as

@udunsigned decimal and returns a list of its digits.

One verbose Hoon program

!:|= [n=@ud]=/ values *(list @ud)|- ^- (list @ud)?: (lte n 0) values%= $n (div n 10)values (weld ~[(mod n 10)] values)==

Save this as a file /gen/num2dig.hoon, |commit %base, and run it:

> +num2dig 1.000~[1 0 0 0]> +num2dig 123.456.789~[1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9]

A more idiomatic solution would use the ^ ket infix to compose a cell and build the list from the head first. (This saves a call to ++weld.)

!:|= [n=@ud]=/ values *(list @ud)|- ^- (list @ud)?: (lte n 0) values%= $n (div n 10)values (mod n 10)^values==

A further tweak maps to @t ASCII characters instead of the digits.

!:|= [n=@ud]=/ values *(list @t)|- ^- (list @t)?: (lte n 0) values%= $n (div n 10)values (@t (add 48 (mod n 10)))^values==

(Notice that we apply @t as a mold gate rather than using the tic notation. This is because ^ ket is a rare case where the order of evaluation of operators would cause the intuitive writing to fail.)

- Extend the above generator so that it accepts a cell of type and value (a

vaseas produced by the!>zapgar rune). Use the type to determine which number base the digit string should be constructed from; e.g.+num2dig !>(0xdead.beef)should yield~['d' 'e' 'a' 'd' 'b' 'e' 'e' 'f'].

Exercise: Resolving Wings

Enter the following into dojo:

=a [[[b=%bweh a=%.y c=8] b="no" c="false"] 9]

Test your knowledge from this lesson by evaluating the following expressions and then checking your answer in the dojo or see the solutions below.

b:a(a [b=%skrt a="four"])^b:a(a [b=%skrt a="four"])^^b:a(a [b=%skrt a="four"])b.a:a(a [b=%skrt a="four"])a.a:a(a [b=%skrt a="four"])+.a:a(a [b=%skrt a="four"])a:+.a:a(a [b=%skrt a="four"])a(a a)b:-<.a(a a)- How many times does the atom

9appear ina(a a(a a))?

The answers are at the bottom of the page.

List operations

Once you have your data in the form of a list, there are a lot of tools available to manipulate and analyze the data:

The ++flop function reverses the order of the elements (exclusive of the

~):> (flop ~[1 2 3 4 5])~[5 4 3 2 1]Exercise:

++flopYourself: Without using flop, write a gate that takes a(list @)and returns it in reverse order. There is a solution at the bottom of the page.The ++sort function uses a

listand a comparison function (like ++lth) to order things:> (sort ~[1 3 5 2 4] lth)~[1 2 3 4 5]The ++snag function takes an index and a

listto grab out a particular element (note that it starts counting at zero):> (snag 0 `(list @)`~[11 22 33 44])11> (snag 1 `(list @)`~[11 22 33 44])22> (snag 3 `(list @)`~[11 22 33 44])44> (snag 3 "Hello!")'l'> (snag 1 "Hello!")'e'> (snag 5 "Hello!")'!'The ++weld function takes two lists of the same type and concatenates them:

> (weld ~[1 2 3] ~[4 5 6])~[1 2 3 4 5 6]> (weld "Happy " "Birthday!")"Happy Birthday!"Exercise:

++weldYourself: Without using weld, write a gate that takes a[(list @) (list @)]of which the product is the concatenation of these two lists. There is a solution at the bottom of the page.

There are a couple of sometimes-useful list builders:

The ++gulf function spans between two numeric values (inclusive of both):

> (gulf 5 10)~[5 6 7 8 9 10]The ++reap function repeats a value many times in a

list:> (reap 5 0x0)~[0x0 0x0 0x0 0x0 0x0]> (reap 8 'a')<|a a a a a a a a|>> `tape`(reap 8 'a')"aaaaaaaa"> (reap 5 (gulf 5 10))~[~[5 6 7 8 9 10] ~[5 6 7 8 9 10] ~[5 6 7 8 9 10] ~[5 6 7 8 9 10] ~[5 6 7 8 9 10]]The ++roll function takes a list and a gate, and accumulates a value of the list items using that gate. For example, if you want to add or multiply all the items in a list of atoms, you would use roll:

> (roll `(list @)`~[11 22 33 44 55] add)165> (roll `(list @)`~[11 22 33 44 55] mul)19.326.120

Once you have a list (including a tape), there are a lot of manipulation tools you can use to extract data from it or modify it:

- The ++lent function takes

[a=(list)]and gets the number of elements (length) of the list - The ++find function takes

[nedl=(list) hstk=(list)]and locates a sublist (nedl, needle) in the list (hstk, haystack) - The ++snap function takes

[a=(list) b=@ c=*]and replaces the element at an index in the list (zero-indexed) with something else - The ++scag function takes

[a=@ b=(list)]and produces the first a elements from the front of the list - The ++slag function takes

[a=@ b=(list)]and produces all elements of the list including and after the element at index a

There are a few more that you should pick up eventually, but these are enough to get you started.

Using what we know to date, most operations that we would do on a collection of data require a trap.

Exercise: Evaluating Expressions

Without entering these expressions into the Dojo, what are the products of the following expressions?

(lent ~[1 2 3 4 5])(lent ~[~[1 2] ~[1 2 3] ~[2 3 4]])(lent ~[1 2 (weld ~[1 2 3] ~[4 5 6])])

Exercise: Welding Nouns

First, bind these faces.

=b ~['moon' 'planet' 'star' 'galaxy']=c ~[1 2 3]

Determine whether the following Dojo expressions are valid, and if so, what they evaluate to.

> (weld b b)> (weld b c)> (lent (weld b c))> (add (lent b) (lent c))

Exercise: Palindrome

- Write a gate that takes in a list

aand returns%.yifais a palindrome and%.notherwise. You may use the ++flop function.

Solutions to Exercises

Fruit Tree:

- 🍇

9or-<+ - 🍌

11or->+ - 🍉

12or+<- - 🍏

16or-<-< - 🍋

27or+<+> - 🍊

30or+>+< - 🍑

42or->->- - 🍒

62or+>+>- - 🍍

87or->->+>

- 🍇

Resolving Lark Expressions

> =b [[[5 6 7] 8 9] 10 11 12 13]> -<+<:b6Resolving Wing Expressions

%bweh"no"- Error:

ford: %slim failed: %skrt"four"a="four"- Note that this is different from the above!"four"[[[b=%bweh a=[[[b=%bweh a=%.y c=8] b="no" c="false"] 9] c=8] b="no" c="false"] 9]%bweh9appears 3 times:

> a(a a(a a))[[[ b=%bweh a [[[b=%bweh a=[[[b=%bweh a=%.y c=8] b="no" c="false"] 9] c=8] b="no" c="false"] 9] c=8] b="no" c="false"] 9]Roll-Your-Own-

++flop::: /gen/flop.hoon::|= a=(list @)=| b=(list @)|- ^- (list @)?~ a b$(b [i.a b], a t.a)Roll-Your-Own-

++weld::: /gen/weld.hoon::|= [a=(list @) b=(list @)]|- ^- (list @)?~ a b[i.a $(a t.a)]++lentexpressionsRunning each one in the Dojo:

> (lent ~[1 2 3 4 5])5> (lent ~[~[1 2] ~[1 2 3] ~[2 3 4]])3> (lent ~[1 2 (weld ~[1 2 3] ~[4 5 6])])3++weldexpressionsRunning each one in the Dojo:

> (weld b b)<|moon planet star galaxy moon planet star galaxy|>This will not run because

weldexpects the elements of both lists to be of the same type:> (weld b c)This also fails for the same reason, but it is important to note that in some languages that are more lazily evaluated, such an expression would still work since it would only look at the length of

bandcand not worry about what the elements were. In that case, it would return7.> (lent (weld b c))We see here the correct way to find the sum of the length of two lists of unknown type.

> (add (lent b) (lent c))7Palindrome

:: palindrome.hoon::|= a=(list)=(a (flop a))